Key Opportunities of Private Equity in Asia

Frustrated by years of low volatility in equities markets and barrel-scraping yields in many fixed-income assets across Europe and North America, traditional asset managers, pension funds and sovereign wealth funds, among other institutions, have been exploring the Asia-Pacific region (APAC) for opportunities to boost returns.

Investors have been increasing allocations to closed-end private equity real estate funds that target properties in Japan and Australia, Ho Chi Minh City, Singapore and China. Investors in the region have mostly favoured the office sector, but also expect investments in industrial and logistics spaces to perform well.

After they settle on a market and a sector, though, investment managers are increasingly looking for fund administrators that can provide end-to-end services for the region, ranging from accounting to financing. Leveraging the right investment strategy and fund service provider, such as an administrator, can help enhance investment opportunities in the most promising market segments of a burgeoning region.

A region of different cycles

Industry watchers have been heralding the coming peak of real estate market cycles across the globe for several years. But real estate in the APAC region continues to generate solid returns roughly a decade after the Global Financial Crisis, according to a PwC and Urban Land Institute (ULI) study. Across markets and sectors, total returns in APAC were expected to reach 8.7 per cent last year, according to M&G Investment Management.

Investors are monitoring closely how the region’s diversity plays into their calculus for investing in markets and sectors that are crossing different points in their respective cycles. Broadly, the region’s economies continue to grow. Investors disagree, though, as to how much longer that will be the case and how APAC’s significant endogenous and exogenous risks will affect real estate.

Among risks, the coronavirus leads most conversations today. Although Covid-19 infections continue to spread, hampering growth across the region and spooking investors, particularly in equities, many economists predict the virus will have a limited impact on investments with longer time-horizons. The coronavirus doesn’t present a direct threat to Asian real estate markets, but its full impact on real estate investments is more difficult to predict at this early stage.

Investors are also watching real estate values closely to determine whether prices are cresting in specific markets or sectors. They’re concerned about the mixed levels of regulatory and legal protections throughout APAC countries, as well as how much US-China trade tensions are slowing economic growth and capital flows, more generally. Their most germane fears, though, concern market overcrowding, which makes deals more expensive and harder to source.

Finding the deals

Despite the litany of risks across Asia-Pacific, private equity firms that raise capital in a fund to buy and develop, improve or operate properties and then sell them to generate higher returns mostly remain determined to put capital to work in the region. Still, private equity real estate fundraising and deal flow fell in 2019, according to the latest McKinsey report on private markets.

But last year’s declines haven’t erased the recent growth the region has seen. Private market fundraising in Asia – of which private equity real estate represents a significant portion – grew at an average of 7 per cent annually between 2013 and 2018.

In particular, pension fund allocations to private markets – which include real estate, private equity, venture capital, private debt and infrastructure have leapt to 23 per cent from 6 per cent since 1999, according to a Willis Towers Watson Thinking Ahead Institute study.

Private equity real estate investors in closed-end funds have attracted large asset managers, such as BlackRock and Aberdeen Asset Management, as well as Malaysian sovereign wealth funds. They’ve been looking at logistics space in Japan; office and logistics in Australia; luxury housing and office in Singapore; and affordable and mid-market housing in Ho Chi Minh City. These investors also are calculating that U.S.-China trade war-induced slumps in Chinese markets could present buying opportunities, according to PwC and ULI.

(Retrieved From: PEWire)

After roaring ahead in 2017 and 2018, Asia-Pacific private equity (PE) investment declined year-on-year as the region’s largest market, Greater China, slumped. There, the boom that produced record deal value for two years running ended abruptly: Deal activity and exits plunged, pulling down the region’s performance. In all other geographies, by contrast, investment grew or was on par with the average of the previous five years.

Domestic factors played a large role in China’s reversal. Real GDP growth in the second half of 2019 slowed to 6%, the lowest rate since the first quarter of 2009, in the midst of the 2008–2009 recession. The ongoing low level of renminbi-based fund-raising undercut investment activities by reducing dry powder. Ongoing trade tensions with the US and social unrest in Hong Kong also undermined the economy and investor confidence. Bain’s 2020 Asia-Pacific private equity survey, conducted with 175 senior market practitioners, shows that macro softness was the No. 1 worry for PE funds focused on Greater China.

Beyond the contraction in Greater China—and perhaps more worrying—the sharp drop in exits across the region meant that cash flow for limited partners (LPs) in late 2018 and 2019 was negative for the first time since 2013. General partners (GPs) already had trimmed their portfolios in 2018 when exit values hit a record high, but an uncertain macroeconomic outlook, tepid M&A activity and an erratic stock market also discouraged funds from pursuing exits.

Despite warning signals, several positive trends stood out. Solid investment growth in other markets helped maintain Asia-Pacific’s heavyweight status in the global private equity market (see Figure 1.1). The asset class also remained a popular source of capital in the region. It made up 17% of the Asia-Pacific merger-and-acquisition (M&A) market, slightly down from the previous year, but up from an average 14% in the previous five years.

Importantly, returns remained strong, with the top quartile of Asia-Pacific-focused funds forecasting a net internal rate of return (IRR) of 16% or higher, and private equity outperformed public-market benchmarks by at least six percentage points across 1-, 5-, 10- and 20-year periods.

Looking forward, the region’s general partners face a broad set of challenges. Widespread uncertainty in financial markets, exacerbated by the coronavirus outbreak in China, trade frictions and macroecononic risk paint a more sober picture for the coming year. Any one of those factors could trigger serious economic and social imbalances in the coming decade, changing the investment outlook for countries or regions. As investors weigh those risks, many are becoming more cautious.

But uncertain times also create opportunities for those who are well-prepared. Leading funds are anticipating disruption and targeting sectors likely to thrive in a downturn. Bain research shows that in hard times, the performance gap between winners and losers widens. Top performers adjust their strategies before the market shifts, increase their control over deals and manage their portfolios more actively. Reducing risk while redoubling their focus on opportunities helps GPs outperform even in an unpredictable market.

As PE funds seek out new pockets of growth, many are eying Internet and tech-related assets. Though investors worry about the risk of a market correction, the sector offers faster-than-average growth and was widely recession-resistant during the last global financial crisis. But given the record high prices for these assets, ferreting out smart investments requires a special set of skills and capabilities. Winning GPs are investing in talent, building partnerships, honing their approach to deal assessment and ensuring companies with new technologies have a path to commercialization. In section 3, we’ll look more closely at how leading PE funds are navigating a riskier investment landscape, and their changing focus within the Internet and tech sector.

2. What happened in 2019?

Asia-Pacific’s private equity markets went their own way in 2019, with diverging tales of growth and contraction. Greater China was hit hard by macroeconomic uncertainty and a reduction in megadeals, while investment activity flourished in most of the other markets.

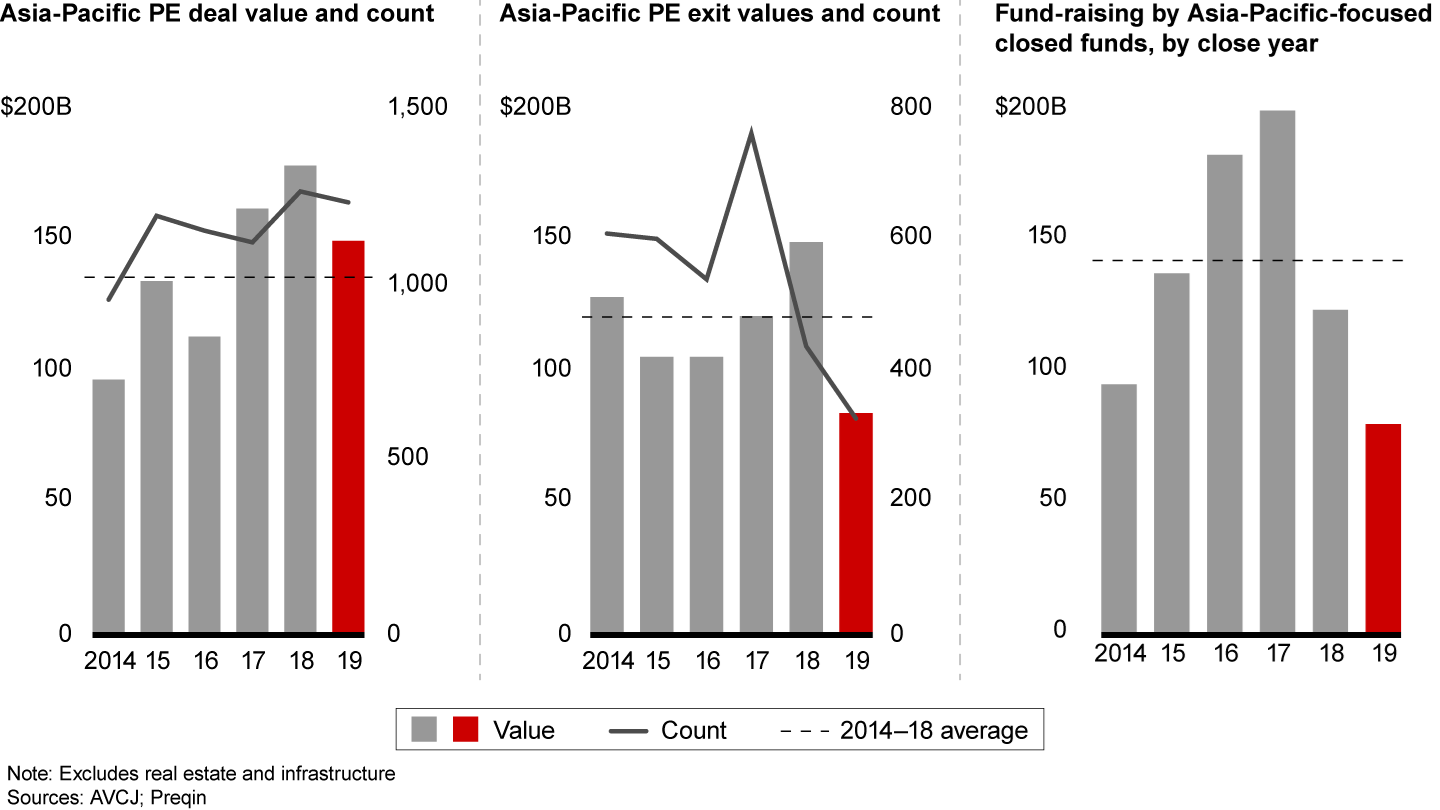

With Asia-Pacific’s powerhouse market down, investment decelerated to $150 billion. Exits took a hit across the region and sank 43% from a record high in 2018. Overall, fund-raising in 2019 tumbled 45% from the historical five-year average. Restrictions on renmimbi-denominated funds continued to hamper activity in China (see Figure 2.1). And with a record $388 billion in dry powder available, GPs didn’t feel pressure to raise new funds.

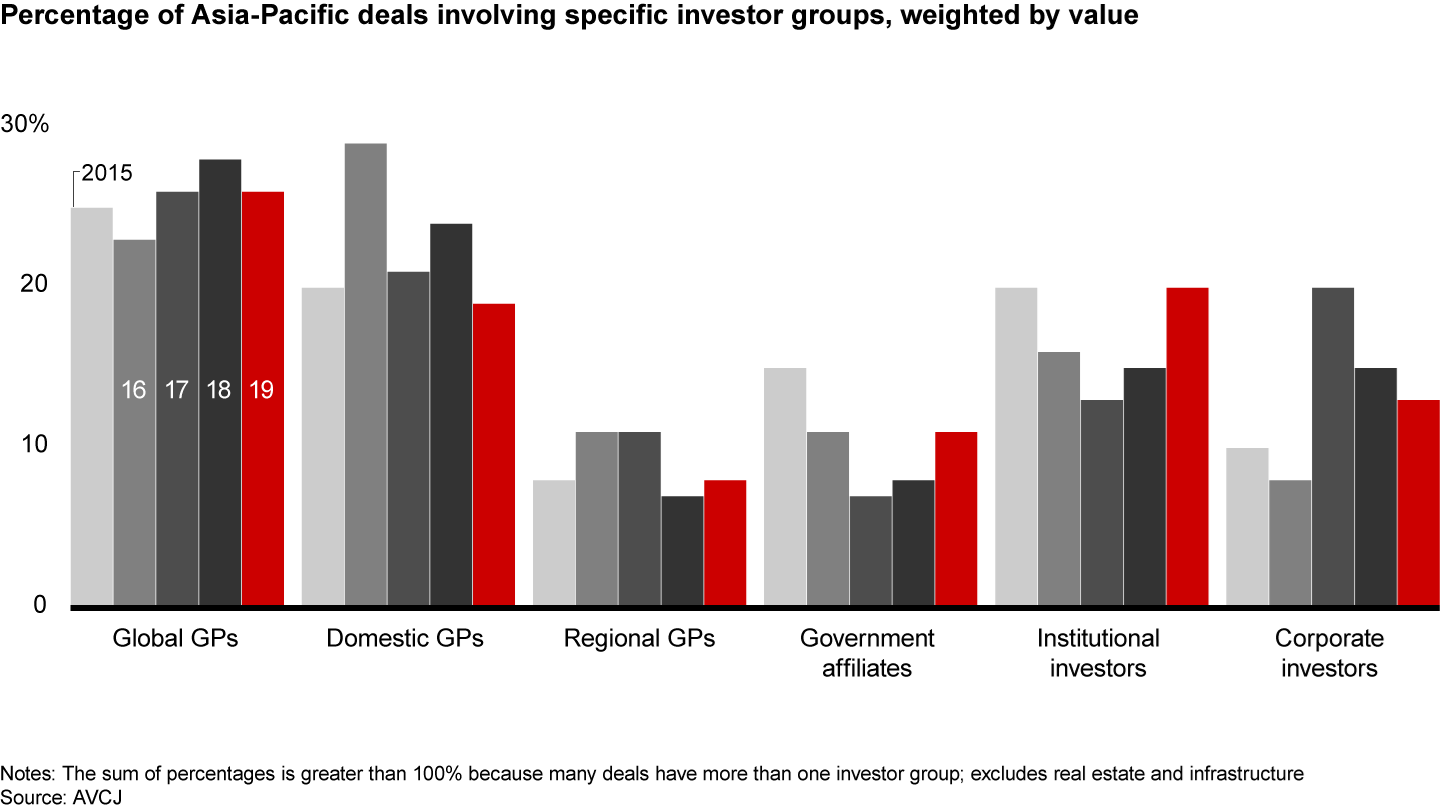

Global and domestic GPs were more active than institutional and corporate investors in the region, although domestic GPs’ share of deals fell to a five-year low. The 2019 drop in domestic GPs reflects a decline in domestic funds’ activity across all geographies, particularly China, where local funds are traditionally strong. Corporate investors retrenched, taking part in only 13% of deals, well below 2017’s high of 20%.

The most active Asia-Pacific investors were global general partners.

What’s clear is that a tougher investment landscape has done nothing to diminish competition in Asia-Pacific. Eighty-five percent of PE funds say that rivalry for the best deals has increased in their primary market, with other GPs considered the biggest competitive threat, followed by corporate investors and LPs investing directly. The number of active investors in 2017 to 2019 reached a record 3,300, compared with 2,700 for 2015 to 2017, though the growth has plateaued.